What Is Muscle Hypertrophy & How Does It Work?

Do you know what muscle hypertrophy means?

Even if you haven’t heard the term before, you can probably make a pretty good guess…

Simply put, muscle hypertrophy is just the technical term for muscle growth.

But while that part is fairly clear cut, the wider topic itself can be pretty complex.

Yup, if you search online, you’ll find hundreds of different theories on the most effective ways to achieve hypertrophy (many of which are completely bogus).

And, to complicate things even further, there isn’t just one kind of muscle hypertrophy…

Nope, there are actually 2 distinctly different types of hypertrophy – sarcoplasmic hypertrophy and myofibrillar hypertrophy.

Confused yet?

Not to worry – in this article I’m going to break down exactly what you need to know about muscle hypertrophy, so that you can focus on building muscle and strength in the most effective ways possible.

Understanding The Different Types Of Hypertrophy

As I mentioned above, there are 2 fundamentally different types of muscle hypertrophy.

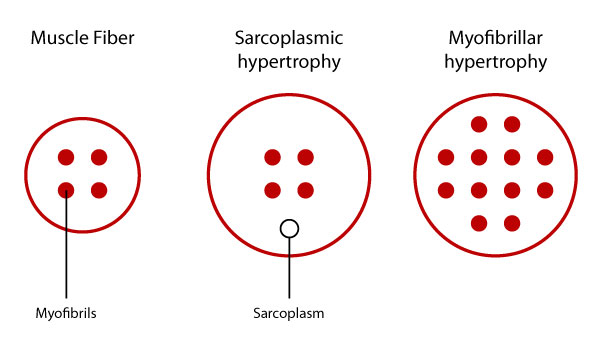

But before I get into each of them, I want you to have a better visual sense of what this all looks like.

The left-most picture is an illustration of a muscle fiber.

Inside the muscle fiber, you have what are known as myofibrils (shown as little red dots).

You can think of these myofibrils as the part of the muscle fiber that is capable of generating force.

Surrounding each of these clusters of myofibrils is something known as sarcoplasm.

You can think of sarcoplasm as the gel-like substance that surrounds the inside of various cells in our bodies, including muscle cells.

In this context, the 2 different types of muscle hypertrophy – known as sarcoplasmic and myofibrillar hypertrophy – are a lot easier to understand.

Sarcoplasmic hypertrophy is simply when there is an increase in the sarcoplasm part of the muscle cell, which is comprised of water, collagen, glycogen, and various minerals.

However, since the number of myofibrils haven’t increased, sarcoplasmic hypertrophy doesn’t lead to gains in strength, even though the muscle itself gets bigger.

In fact, this is the type of temporary muscle hypertrophy that can occur when you supplement with creatine (due to increased water uptake by muscle cells) or if you increase the number of carbohydrates in your diet (due to increased muscle glycogen).

In contrast to this, with myofibrillar hypertrophy the number of myofibrils increase along with the sarcoplasm (as you can see in the right-most illustration).

Therefore, unlike sarcoplasmic hypertrophy, myofibrillar hypertrophy produces both gains in size AND strength.

For this reason, myofibrillar hypertrophy is generally considered to be more desirable than sarcoplasmic hypertrophy.

Is This Why You Sometimes See Big People That Aren’t That Strong?

Interestingly, all of this offers a possible explanation for the cases where muscle size doesn’t correlate to strength.

Have you ever seen someone who looks like they could bench press a house, but has trouble with 225 lbs.

Or, on the opposite end of the spectrum, someone who is able to squat a ton of weight, even though they are relatively small.

Well, some experts believe that this is actually a result of the differences between the 2 types of hypertrophy.

The bigger, relatively weak person would have a greater degree of sarcoplasmic hypertrophy (think the typical bodybuilder physique), whereas the smaller, relatively strong person would have more myofibrillar hypertrophy (like many powerlifters).

However, another plausible explanation for this is that strength athletes – such as powerlifters or olympic weightlifters – tend to focus on a limited number of specific exercises, and train them very consistently.

This frequency of training leads to neuromuscular adaptations for these specific movements, allowing such athletes to lift weight more with the amount of muscle that they already have.

In short, their muscles become more efficient at weight lifting, even if the number of myofibrils in their muscle cells remain the same.

At the moment, there is insufficient evidence to make any firm conclusions here, but it is an interesting topic that will hopefully inspire more studies in the future.

And, of course, I should mention that it has long been speculated that taking steroids will increase sarcoplasmic hypertrophy (although the studies on this are inclusive).

So How Do I Maximize A Specific Type Of Hypertrophy?

At this point, there really isn’t sufficient evidence that you can.

That is to say, there isn’t an established training protocol that will produce more sarcoplasmic hypertrophy than myofibrillar hypertrophy, or visa versa.

But at the end of the day, this really doesn’t matter too much for the average person lifting weights, who wants to get stronger and bigger.

For natural weight lifters, strength is highly correlated to muscle size, so the best thing to do if you want to build muscle is to focus on getting stronger.

For this reason, in order to maximize muscle hypertrophy, you’ll want to follow a routine that is progressive overload-oriented.

You’ll also want to make sure to track your workouts, and try to get the appropriate amount of rest time between sets.

And, of course, in order to build muscle properly, you’ll have to focus on your diet as well (this article is a good place to start).

So, in closing, my advice for most people would be not to worry about trying to optimize for a specific type of hypertrophy.

For one, there isn’t a proven way to do so – and secondly, it isn’t what you should be focusing your energy on.

This is especially true if you’re newer to working out; there is no need for you to overcomplicate things.

So if you’ve only been working out for a few years or less, just focus on lifting heavy, making steady strength progressions – and, of course, getting a handle on your diet – and you should be able to get bigger and stronger month after month.